In Search of a 'Feminist Sensibility': Two Shorts By Deborah Stratman and Lynne Sachs

Vever (for Barbara) dir. Deborah Stratman, 2019 Carolee, Barbara & Gunvor dir. Lynne Sachs, 2018.

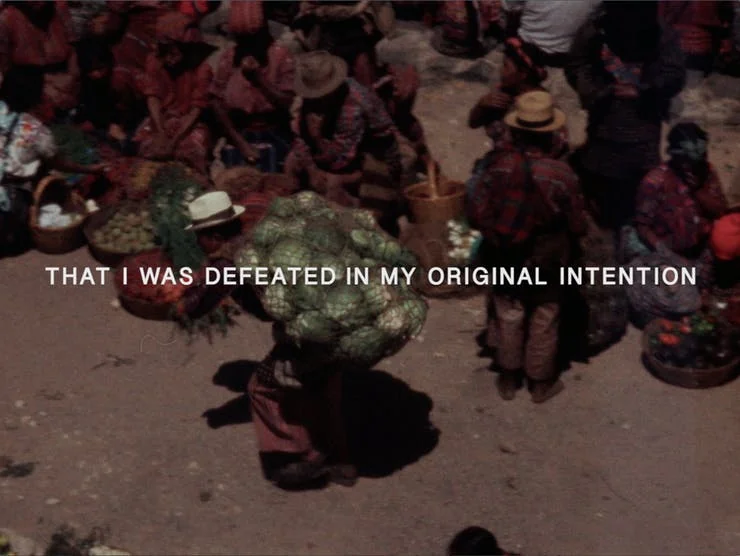

When the Bay Area lesbian scene of the Seventies felt like it was closing in around her, Barbara Hammer hit the road. She took her motorcycle and a loaded camera to Guatemala, vowing to stay until all her film had been exposed. But when Hammer left Guatemala in 1975, her film all used up, her experience there had failed to conform to the narrative she’d had in mind. The artistic result of her cross-cultural soul search fell short. While there’s certainly a history of spurned lovers turning to foreign, 'primitive' locales to artistically render their heartbreak against ethnographically-tinged changes of scene, it isn’t exactly Barbara’s speed.

Neither was it Maya Deren’s. In the '50s she travelled to Haiti, capturing 18,000 feet of documentary footage for what would eventually become Divine Horsemen. Editing stalled; the project failed to reach completion in her lifetime. Reflecting on the experience, Deren wrote: “It was only after I had conceded my defeat as an artist, my inability to master the material in the image of my own intention, that I became aware of the ambiguous consequences of that failure.” This, along with other excerpted musings on the trip, is paired with Hammer’s previously-unseen footage in Deborah Stratman’s Vever (For Barbara) (2019), which premiered at this year’s Berlinale. Interweaving their accounts of failed soul-searches – Deren’s in writing, and Barbara’s through voice-over taken from a phone call – Stratman constructs a lineage of feminist filmmakers spanning three generations. The implied relationship between them is that they share a certain sensibility, more taciturn than, say, Marker's Sans Soleil.

Is this a feminine sensibility? A similar question is at play in _Carolee, Barbara & Gunvor _ (2018), Lynne Sachs’ portrait of three trailblazing experimental filmmakers, which premiered at MoMa's Documentary Fortnight last year. In a Derenesque wink, the opening image is a cat, as Schneemann’s voice drifts in from the space offscreen. She remembers her first camera – a Brownie – and how holding it made filmmaking feel like “an inevitability”. Sachs’s camera, as if searching for Schneemann, pans around an empty room—a nod to Deren’s Meshes, and __ tinged with Akerman, too. Before any of the film’s titular subjects even appear on camera, _Carolee, Barbara & Gunvor _pulsates with the energy of feminist experimental cinema’s kindred trailblazers. Common threads are explicated, teased out by the subjects’ accounts, yet left open-ended as brevity is forced by the film’s short runtime.

In her section of the triptych, Schneemann recalls the challenge of convincing a male friend to lend her his Bolex: he resisted “as if I would bleed on this precious machinery”. She admits that she didn’t really know how to use it. Yet we know that the spirit of determination – so distinct in her oeuvre – won out, because now she’s on the other side of the camera. Next, we see Hammer. In contrast to the disembodied voice from Vever – made frail by poor cell connection and increasingly-advanced cancer – she is vivacious, running through the West Village, clowning for the camera. She recounts a foundational anecdote of her practice: on a detour from another motorcycle ride she was sidetracked by a crop of leaves in striking red. As if compelled by the goddess, she took out a bifocal lens from her optometrist and placed it in front of the camera, moving while she filmed. The finished project was a sublime manifestation of exactly how she’d felt when the leaves first caught her eye. , This embrace of openness and contingency was, for Barbara, fundamentally feminine – “I could make the inside of myself show on the outside” – and a release from the schizophrenic pull of rigidly-gendered rules for expression.

The last and longest section of Sachs’s film opens with a series of lingering close-ups of flowers. “After seeing a few of Bruce Bailey’s films, I understood that I, also as a single artist, could try.” In her childhood village in Sweden, Gunvor Nelson paces herself through what she has decided will be the final three projects of her career. There is a certain and deliberate slowness in her approach. She struggles to find tech support for her DSLR, but adapts to this challenge, finding eagerness and excitement in “calmly working” with stills. Sachs opts for a drawn-out rhythm in this vignette, as meandering shots of the surrounding nature recall the particular intimacy of Nelson’s work. This extends to her current process: even amidst technological change, she is invested in listening to her images, we sense, not bludgeoning them into some preordained vision.

These two shorts give us insight into seven women: Barbara Hammer, Maya Deren, Carolee Schneemann, and Gunvor Nelson as subjects and speakers; Lynne Sachs and Deborah Stratman from behind the camera. Watching both films, I wonder what connections there are to be drawn. Does the recent surge in filmic portraits of female trailblazers point towards a 'feminine sensibility', long overdue for historical recognition? I’m hesitant to speak about any 'shared themes' across the layered, nuanced careers that constitute this genealogy, lest these similarities be construed as an essentialised roadmap. How can we identify the beauty that comes from rejecting the strictures of masculine ways-of-being in the world without mummifying it, crystallizing these artists’ irreducible vibrancy into a prescriptive binary formula?

The key might lie in situating their work within experimental cinema’s challenging, unfeminist history. Reflecting on her mid-Sixties collaboration with Stan Brakhage, Schneemann laments: “Whenever I collaborated, went into a male friend’s film, I always thought I would be able to hold my presence, maintain an authenticity. It was soon gone, lost in their celluloid dominance.” Cat’s Cradle is hardly the only masterwork of structural film to suggest a sort of Abstract Expressionist-adjacent machismo. Against this backdrop, the nexus of similarities between Schneemann, Deren, Nelson, Sachs, and Stratman becomes explicable not as the record of some intrinsically-female way of seeing and filming the world, but as the product of work : a shared undertaking invested in upending experimental cinema’s more problematic attitudes and replacing them with a new hierarchy of aesthetic values: adaptability, intimacy, and tenderness. Only when we honour these values, in all their many manifestations across these seven artists’ careers, can we begin to construct the kind of feminist genealogy[^1] that film history so urgently requires.

1 This term was proposed by Lucy Bolton in Film and Female Consciousness: Irigaray, Cinema and Thinking Women (Palgrave Macmillan, 2011) Deborah Stratman's Vever (For Barbara) premiered at the Berlinale last week. Lynne Sachs's Carolee, Barbara and Gunvor is available to watch here.